monomer

This is the page devoted to a little introduction of how polymers are made. A chemical reaction that makes polymers is called a polymerization. There are many of these reactions, and they come in all kinds. But all polymerizations have one thing in common: They all start with small molecules, and join them into big giant molecules. We call the original small molecules monomers. But they can join in many different ways. People like to categorize things, so Immanuel Kant tells us, and polymerization reactions are not exempt from our classifying urges. So we classify these polymerization reactions.

We aren't going to list these classifications just yet.

But just coming up with a few categories isn't enough for us. We have to come up with different classification systems. And the different systems can often be confused. So we're going to try to make it clear as possible by listing the different systems right up front. The first system is the Addition-Condensation system.

This system divides polymerizations into two kinds, and if you're really clever you've probably figured out that those two kinds of polymerization are

Now, we call a polymerization an addition polymerization if the entire monomer molecule becomes part of the polymer. We call a polymerization a condensation polymerization if part of the monomer molecule is kicked out when the monomer becomes part of the polymer. The part that gets kicked out is usually a small molecule like water, or HCl gas. Such small molecules condense on things as tiny droplets, hence the name. Let's look at some examples to illustrate the point.

When ethylene is polymerized to make polyethylene, then every atom of the ethylene molecule becomes part of the polymer. The monomer is added to the polymer outright. You might say that an addition polymer is like a good friend who accepts

everything about you, the pleasant and the unpleasant alike.

But a condensation polymer is more like a snotty social club that says, "Sure you can join, but only if you ditch those friends of yours". You see, in a condensation polymerization, some atoms of the monomer don't end up in the polymer. When nylon

6,6 is made from adipoyl chloride and hexamethylene diamine, the chlorine atoms from the adipoyl chloride, each along with one of the amine hydrogen atoms, are expelled in the form of HCl gas.

Because there is less mass in the polymer than in the original monomers, we say that the polymer is condensed with regard to the monomers. The byproduct, whether it's HCl gas, water, or whatnot, is called a condensate.

The Bottom Line

Want the short version? Condensation polymerizations give off byproducts. Addition polymerizations don't.

Now let's talk about the next system of classification: The Chain Growth - Step Growth system.

The other system of classifying polymerizations again divides polymerization reactions into two categories, and those are, all together now:

and

Very good. Now the differences between a chain growth polymerization and a step growth polymerization are a little more complicated than the differences between an addition polymerization and a condensation polymerization. It goes something like this:

In a chain growth polymerization, monomers become part of the polymer one at a time. Pretty simple, huh? To show you how it works we've got a picture of a chain growth polymerization here, namely the anionic polymerization of styrene to make

polystyrene. Take a look at it.

But in a step growth polymerization, things are more complicated. Let's take a look at the step growth polymerization of two monomers, terephthaloyl chloride and ethylene glycol, to make a polyester called poly(ethylene terephthalate). The first thing that happens is that the two monomers will react to form a dimer. Sounds simple enough.

Now at this point in a chain growth system, only one thing could happen: a third monomer would add to the dimer to form a trimer, then a fourth to form a tetramer, and so on. But here, in the free land of step growth polymerization, that dimer can do a lot of different things. It can of course react with one of the monomers to form a trimer:

But it can do other things, too. It may react with another dimer to form a tetramer:

Or it may even get really crazy and react with a trimer to form a pentamer.

Making things more complicated, these tetramers and pentamers can react to form even bigger oligomers. And so they grow and grow until eventually the oligomers are big enough to be called polymers.

Just think of the way your bank keeps merging with other banks and getting bigger and bigger, and you'll get the idea.

The main difference is this: In a step growth reaction, the growing chains may react with each other to form even longer chains. This applies to chains of all lengths. The monomer or dimer may react in just the same way as a chain hundreds of monomer units long. But in an addition polymerization, only monomers react with growing chains. Two growing chains can't join together the way they can in a step growth polymerization.

Things are actually much more complicated than we've described them so far. And if you really want to get to the "bottom line," you have to look at the details of kinetics and chain growth. Let's talk a little about molecular weight and how it grows with conversion.

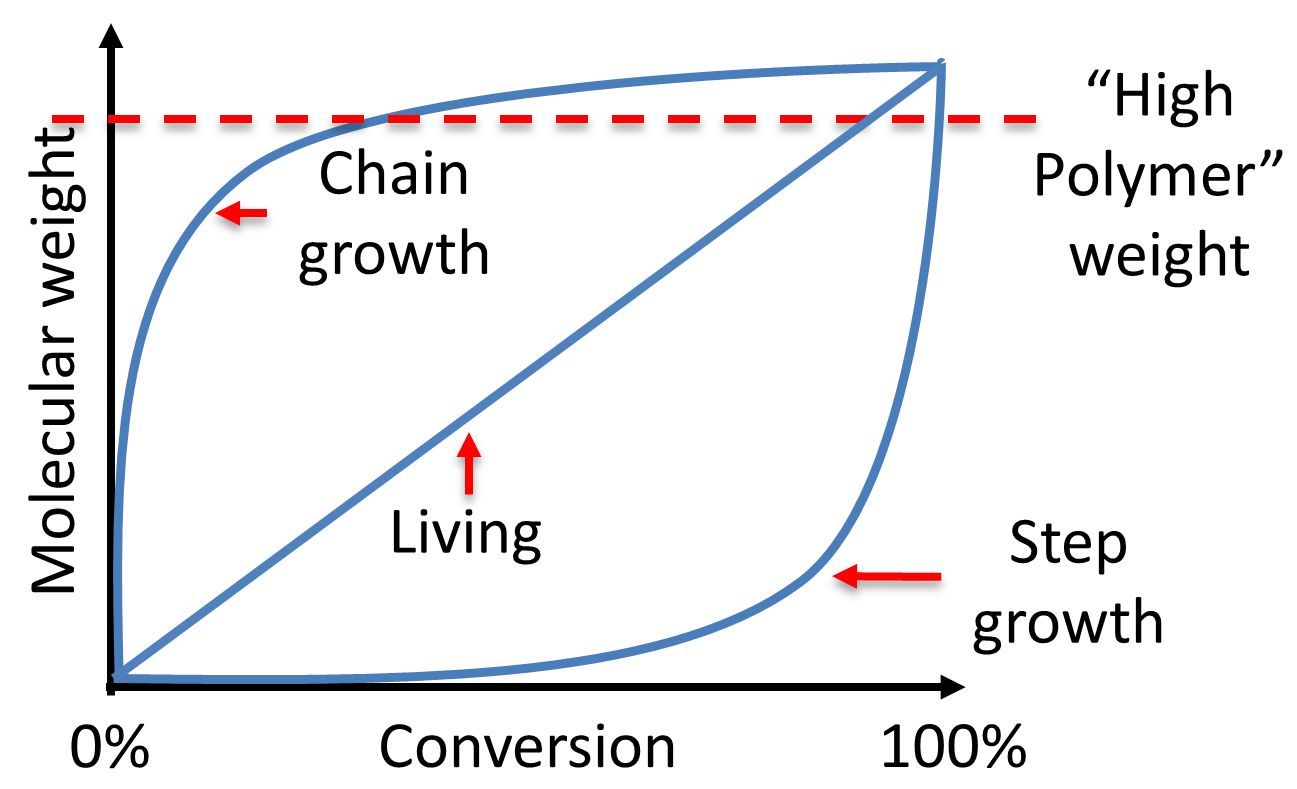

First we have to define conversion. In a normal organic reaction, conversion refers to how fast one or more of the reactants gets used up, converted to whatever product you're aiming at. With polymers it's not so simple. Turns out in step growth polymerization, your main reactant (the "monomer" or "monomers") gets used up early on, way before you have molecular weights needed for useful properties (see the graph below). For step growth polymerization, then, we're better off talking about conversion of the reactive groups involved. For example, in polyester formation, that could be either or both the acid groups and the alcohol groups. And the fact that there are two each on the acid and alcohol monomers further complicates things (that we won't go into right now).

It gets even stranger when we look at "conversion" in a chain growth polymerization. Here monomer only reacts with an active chain end but the kinetics are such that chain growth to high molecular weight is fast for any GIVEN growing chain. This leads to the interesting paradox that molecules that are present in a typical chain growth polymerization are either monomer or high molecular weight polymer. Radical polymerizations behave this way. And near the end of polymerization, when the rate of reaction (i.e., conversion of monomer to polymer) slows way down, you STILL have monomer around. It's almost impossible to get rid of all of it. See the plot in the graph above for "chain growth."

You'll notice on the graph there's a straight line labeled "living polymerization." It summarizes how molecular weight grows with conversion for polymerizations that have a special set of properties. For this kind, the only polymer chains growing during reaction all start almost at the same time. Unlike radical polymerization (where growing chains terminate continuously while new chains are started, also continuously), this means that all chains grow at the same rate. Thus, molecular weight builds slowly with conversion but not as slowly as with step growth. And here's the important point about living polymerizations: even if all or most of the monomer is used up, the chains can STILL react. They just sit there, waiting patiently like a New York bus rider ready for the next bus, till something happens. That something could be a quenching agent that kills the living end. Or that something could be the addition of more monomer so that polymerization picks right up again. Most important is the fact that the next batch of monomer added could be the same OR different from the first batch. That's how you make "block" copolymers, folks.

Now I'm sure a lot of you bright people out there noticed that our step growth polymerization to make a polyester produced a byproduct, HCl gas. This of course will make it a condensation polymerization as well as a step growth polymerization.

You may have also noticed that our chain growth polymerization of styrene did not produce a byproduct. Yes, this is an addition polymerization in addition to being a chain growth polymerization.

It's easy to conclude here that a step-growth polymerization and condensation polymerization are the same thing, and that a chain growth polymerization and an addition polymerization are the same thing. But this just isn't always true. There are addition polymerizations that

are step growth polymerizations. One example is the polymerization that produces polyurethanes. There are also condensation polymerizations that are chain growth polymerizations. Trying to reconcile the chain growth-step growth classification system and the addition-condensation classification system is really a waste of time. Each has its own criteria, and the distinctions made by one system are not always going to be the same as the distinctions made by the other.

So don't try to reconcile the two systems. Just know that polymerizations can be step growth or chain growth, and they can be condensation or addition.

The Addition-Condensation System

Addition Polymerization

Condensation Polymerization

The Chain Growth - Step Growth System

Chain Growth Polymerizations

Step Growth Polymerizations

The Bottom Line: It's Complicated

Image provided by Prof. Elizabeth S. Sterner at Lebanon Valley College

Irreconcilable Differences

|

Return to Level Four Directory |

|

Return to Macrogalleria Directory |